By David Finkelhor, Special to CNN

June 20, 2012 -- Updated 1335 GMT (2135 HKT)

Penn State students gather in November in the wake of abuse accusations to express solidarity with the alleged victims.

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- David Finkelhor: Abuse victims may be watching Sandusky trial to see how victims are treated

- He says good and bad news. Good: Victims today far more likely than in past to tell someone

- He says teachers, cops, communities far more clued in, responsive on child sex assault

- Finkelhor: Bad news is judge wouldn't let victims testify anonymously; this potentially hurtful

Editor's note: David Finkelhor is professor of sociology and director of the Crimes against Children Research Center at the University of New Hampshire.

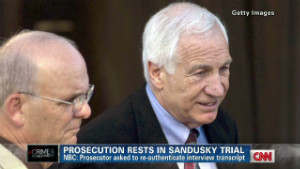

(CNN) -- If you are a survivor of sexual abuse who has not yet reported, you may be attending closely to the trial of former Penn State football coach Jerry Sandusky to see what happens to those who do. The news is both good and bad.

You see some courageous men being taken seriously by prosecutors and journalists. But you see a degree of potential exposure that few victims would want to face, and that we could do a better job of preventing.

First, the better news: We all know that sexual abuse is still a crime that is mostly unrevealed. But progress has been made.Comparisons of recent surveys to those from the 1980s show far more victims today say they reported or that someone in authority found out.

Yet boys are still disproportionately less likely to report, for some of the reasons showcased in this trial: the fear that others will not believe they are really victims, and the fear that they will be stigmatized as wimpy and/or homosexual.

So a case such as this with male victims coming forward, explaining how conflicted they felt, why it took them so long, what it did to their lives, but nonetheless giving convincing testimony that has clearly been believed by the prosecutors and much of the press, this certainly must give other boys and men some sense of possibility.

Indeed, that this case is being prosecuted at all shows how much has changed. People in law enforcement and the public at large now know that boys do indeed get abused. Thousands of professionals have gotten specialized training in how to identify victims, how talk with them and how not to exacerbate the harm when interviewing.

Specialized Child Advocacy Centers exist in more than 600 communities to make the process more child friendly. These trained police and prosecutors do understand why it is so hard to report, why the testimony sometimes changes and how the fact of participating in the sexual activity doesn't signify enjoyment or lack of harm. Growing numbers of women in law enforcement have certainly helped.

But we still have a long way to go.

The possibility of your abuse ending up fodder for a national media frenzy that rivals the Super Bowl would hardly seem comforting to most potential disclosers. The possibility of having your lifelong identity become "that kid who was molested by that coach" would be terrifying.

In that light, perhaps the most discouraging news for survivors in the trial so far was the refusal of the judge to allow the victims to testify anonymously.

This ruling would seem callous. Lots of other countries have built inlegal protections that prevent the media and other court participants from learning the names of child victims of sexual assault. Even in the United States we have protections against the disclosure of the names of juvenile offenders. The notion behind that is that young people can be permanently stigmatized by such notoriety. Why not victims, too?

True, many news outlets have policies to avoid reporting the names of sexual assault victims. But it is an entirely voluntary policy, proudly flouted by some outlets. Studies have shown that information that could readily identify victims appears in 37% of news articles that report on child sexual victimization. So far, the names of the Sandusky accusers have not gotten widespread circulation. But they could.

What was the judge's rationale for denying what would seem like such a reasonable request?

"Secrecy is thought to be inconsistent with the openness required to assure the public that the law is being administered fairly and applied faithfully," Judge John Cleland wrote in his order dismissing the request. "Consequently, there must be justifications of public policy that are very deep and well-rooted to support any measure which interferes with the public's ability to observe a trial and to make their own judgments about the legitimacy of their legal system and the fairness of its results."

But there are. An enormous quantity of research shows sex crimes against children to be particularly traumatic, and aspects of the court experience to be a contributor to the trauma.

Allowing victims to testify anonymously would not truly undermine the openness crucial to make a judgment about the fairness of the system. The victims still have to testify publicly, still have to be confronted by the defense, still have their credibility tested in the eyes of the jury and the media.

Perhaps the judge was afraid of creating a basis for the appeal of a guilty verdict. But that only illustrates how the protection of victim identities needs to be better enshrined in law and practice so it is not seen as a risky anomaly.

However the rest of the trial goes, we we must continue to commit ourselves to building a justice system that takes into account the reasonable needs of child victims for privacy and protection. It is one of the biggest things we can do to help victims come forward and stop abusers after the first rather than the 10th victim.

No comments:

Post a Comment